A Primer on Structural Hedges - the basics

The key to understanding UK banks in the next 2-3 years

As a bank sell-side analyst if I had a pound for every time I received a question on structural hedges in recent years I’d be retired. That investor demand in part reflects the structural hedges importance to the domestic UK bank equity story and in part their perceived complexity. The aim in this blog is to hopefully shed some light on the moving parts and to demonstrate that, at their core, the hedges are not complicated at all, albeit observers are often slightly hamstrung by poor company disclosure.

I’m actually going to write this primer in two separate blogs. This one will deal with the basics and the second blog to be published shortly will look more closely at the current positions of the UK banks and the outlook for the next 2-3 years and what nuances readers should watch for.

1. Why do structural hedges matter?

With no apologies, I’m going to start at the end. I think it’s important to set out the context for writing this primer, to answer the question “why do they matter?”. In the chart below I show the aggregate Net Interest Income growth for the three large UK domestic banks - Barclays, Lloyds and NWG - using company consensus for 2025e-27e and comparing with the increase in the gross income contribution from the structural hedge income (using actual data for 2024 and my estimates for 2025-27e).

What should be clear from this chart is that:

The increasing contribution from the structural hedge is substantial; averaging GBP3bn per annum for the period 2024-27e and

The structural hedge is the primary driver of interest income growth. In 2025e to 2027e readers should think of the structural hedge increases as being the primary driver of net interest income for the UK domestic banks (and with that likely improved ‘returns on tangible equity’ (ROTE).

Structural hedges really do matter, so it is worth understanding the broad dynamics (and I promise to save the nitty gritty to the end of this piece!)

Author’s note: for those who are curious, UK bank NII was depressed in 2024 by a combination of lower rates, weak volumes and mortgage repricing. Even a strong structural hedge improvement was insufficient to offset those factors.

2. Back to the beginning - why do the banks have structural hedges?

To cut to the chase, Structural hedges are designed to reduce interest rate sensitivity. But why do banks need them? I’ll illustrate the problem with an example - imagine you set up a bank in the UK tomorrow - let’s give it the catchy name of the “Bank of Rob”.

Step 1 in creating the bank is to find some investors. Lets say they put GBP100 of cash in to provide equity for the Bank, in return you issue them with ordinary shares. You keep that equity in “cash” with the Bank of England (‘BoE’).

Step 2 - you’ve got great ambitions to be the next big thing in lending. But to do that you first need some proper funding; and that invariably means trying to attract deposits that you can then use to make the loans. Editors note: almost every single UK bank start-up begins this way, and most haven’t got much beyond the ‘get deposits’ stage; think ING Direct, Standard Life Bank, Icesave, Marcus, Monzo, Revolut and Starling).

Normally collecting in retail deposits as a new bank is easy; - savers don’t worry too much that they’ve never heard of you because they’re protected by the UK Deposit Guarantee Scheme. Hence if you pay a market leading rate the money will likely roll in, albeit it might be costly. But let’s say Bank of Rob gets lucky, instead of paying up for deposits it collects GBP900 of ‘interest free’ current account deposits. In the short term absence of any lending management also park that with the BoE.

That means Bank of Rob’s balance sheet consists of assets of GBP1,000 (cash held on reserve with the BoE) and GBP1,000 of liabilities (GBP100 of equity and GBP900 of customer deposits). Nice and simple, the CFO is pleased.

What would the P&L look like for this bank? The BoE will pay you ‘base rate’ on the cash ‘reserves’ held with it. So at say 4% base rates the Bank of Rob would receive GBP40 of gross interest income each year. And because the Bank of Rob pays 0% interest to the current account depositors or the shareholders equity it’s got zero interest expense. Net interest income is therefore GBP40 (40 minus 0).

In the table below on the left hand side I show how this might translate into a Profit & Loss statement. I’m going to assume zero fee income, modest operating costs (1% of assets or GBP10) and a tax rate of 30%. This business model would produce a post-tax profit of GBP21. And with a GBP100 of equity a ROTE of 21% (ie GBP21/GBP 100). Result? CFO happy, shareholders happy.

But what if base rates don’t stay at 4%? After all, it’s not that long ago we had rates as low as 0.1% (and pre-financial crisis, rates were typically 5-7%). Hence, in the table above, on the right hand side, I’ve also shown two alternative base rate scenarios:

In the first rates fall to 1%. The BoE is now paying you just 1% on the money parked with it so Bank of Rob’s income drops from GBP40 to just GBP10. The costs remain fixed at GBP10. Now suddenly the bank is only at breakeven. Shareholders are angry, the CFO begins to brush up his CV.

Base rates rise to 5%. The BoE now pays you 5% on the reserves, income rises to GBP50 and with costs fixed the Bank of Rob now generates a 28% ROTE. Happy days? Note: it’s beyond the scope of this post, but beware deposit based neo-banks suddenly announcing record profits purely on the back of rising rates in the last 3 years, those could quickly evaporate as rates fall.

While I’ve used a simple example here, the Bank of Rob, all of the UK domestic banks suffer from the same issue; the revenues they generate from reinvesting interest free current accounts and their own equity are potentially base rate sensitive, while the interest cost of those elements remains fixed (albeit at 0%). In the absence of any kind of hedging, when rates are high profitability could be great, but as rates drop that profitability could disappear entirely.

That’s ultimately unacceptable to multiple stakeholders. But in particular regulators will worry about the scenario whereby the UK goes into recession and the BoE cuts base rates to boost the economy. That could see banks suffering a double-whammy of rising credit losses and a sharp drop in revenues from lower rates. Hence the PRA measures the interest-rate sensitivity of the banks regularly and requires the banks to moderate it. We’d also flag that the added volatility in the earnings profile would also be unwelcome from shareholders (who could place a discount on the bank’s valuation to compensate.

3. This is why bank’s use structural hedges

The simplest way to reduce the interest sensitivity in our example above would be remove the held on deposit with the BoE, which earns a ‘floating’ rate dependent on base rates, and instead buy an asset with a ‘fixed’ rate return. That way the income stream is stable rather than jumping up and down. And this is where structural hedges come in.

When I first started as a bank analyst in the 90’s the fixed rate assets used by the banks were predominantly UK Gilts. These had the benefit of being both liquid and, thanks to being issued by the UK government, zero credit risk and hence required no capital backing under the then Basel rules. If we think of our ‘Bank of Rob’ example above, if the GBP1,000 of cash were to be put into say 5 year fixed rate gilts at 4% then the Bank would have predictable earnings for those 5 years, rather than seeing big short term fluctuations as base rates moved around. The CFO could put his feet up.

However there are a some nuances to be aware of:

Reinvestment risk. If all of the cash were invested in a single block of gilts maturing in say 5 years then the bank would be exposed to ‘reinvestment risk’. In other words when the gilts matured after 5 years with the proceeds reinvested in new gilts the bank could see a big jump or fall in revenues depending on how the yield on the new gilts compared to the maturing ones.

To avoid this the banks spread out the gilt investment to produce a smoother profile (often referred to as ‘feathering’). Using the Bank of Rob as an example, day 1 management might invest 1/60th of the cash in 1 month gilts, another 1/60th in 2 months, a further 1/60th in three months etc all the way out to year 5 (month 60). This creates a ‘rolling book’ where 1/60th of the hedge matures each month and is replaced. The result is a smooth yield on the hedge.

Outflow risk. The second risk to the bank is deposit outflows. If Bank of Rob were to see current account outflows for whatever reason it might be forced to sell some of the gilts in its structural hedge to repay the current account holders. Being a forced seller is never a good thing and the bank runs the risk of crystallising losses (if the gilts are worth less now than they were bought for). In microcosm this was essentially the primary driver of SVBs failure in 2023.

Having a rolling book of gilts helps here - each month 1/60th of the book matures and can be used to help with modest deposit outflows. But the primary tool the UK banks to use to reduce risks here is being underhedged; instead of investing for example all of the current account balances in the structural hedge, the banks might invest just 95% of balances - this provides them with a cushion against outflows at the expense of losing some of the interest rate protection if they were fully hedged.

The size of the structural hedges. We can see this under-hedging in Lloyds disclosures (table below). Lloyds gives us the details on what it is hedging in its structural hedge; at 25Q2 GBP30bn of equity, GBP135bn of current accounts and GBP79bn of other savings. And with the bank also telling us how much equity, current accounts and savings balances it has in total, we can work out the percentage that’s hedged (75% of equity, 98% of current accounts and 22% of other savings).

Note: interest-bearing savings accounts typically see a low hedging rate (20-25%) reflecting in part the behavioural characteristics of those deposits - balances tend to be more volatile as customers seek better rates.

Equity is typically invested at a longer duration. While a bank might invest current accounts in 5 year gilts, when it comes to the Bank’s own equity we typically see longer duration hedges (10 years) - this reflects the stability of the equity base - it’s rare to see declines here outside of loss periods/heavy share buybacks. Because of this slightly different dynamic, we increasingly see disclosure from the UK banks of their ‘equity’ structural hedge and their ‘product’ structural hedge (the bit that relates to customer deposits).

Swaps not gilts. I’d flag that approximately 10 years ago the UK banks began moving from gilts to swaps. This move was in part due to a modest capital advantage in doing so and also a degree of added flexibility. At this stage, readers just need to be aware that banks will talk exclusive in terms of swaps in recent disclosures, financially, using gilts or swaps works out almost the same for the bank (and swap yields closely track gilt yields). I will post a small paragraph at the end of this document to quickly explain the economic equivalence.

As an aside does the hedge have to be made up of gilts/swaps? The answer is theoretically ‘no’, any fixed rate asset could be used. Gilts and swaps though have the advantage both of liquidity and a low capital requirement under the Basel rules. But I’m conscious that some banks are almost certainly also including small components of their fixed rate mortgage books within their structural hedges. But economically, its a similar outcome to using swaps and hence I’d urge readers to not spend too much time on this.

What is producing today’s gains?

To summarise, the structural hedges are a rolling book of interest rate swaps that are designed to smooth the impact of interest rate moves on the bank’s revenue streams. More specifically, the ‘product hedge’ which accounts for the majority of the structural hedge, tends to be invested in swaps with a duration of around 5 years whereas the much smaller ‘equity hedges’ tend to be invested at 10 year durations.

A brief history of rate movements. Following the global financial crisis (mid-2007 to around 2010), UK interest rates fell precipitately from a near-6% down to 0.5% in 2009. Base rate remained sub-1% until 2021 when they finally began an upwards trajectory reaching 5.25% in 2023. The yields on 5 year swaps largely reflect money markets expectations for where average base rates will be for the next 5 years. So understandably 5 year swap yields dropped from an already low 1.5% in 2018 to just above zero in late 2020. But from mid-2022 onwards those 5 year swap rates have soared (see chart below).

Without the structural hedges, the UK banks could have seen a dramatic boost in profitability from 2022 onwards as base rates increased (but current accounts typically still paid 0%). But with the structural hedge, a large part of the benefit of those higher rates has effectively been deferred to and in particular 2024-27e. In effect the banks need to wait for their book of swaps to mature and be replaced with new swaps at higher yields.

Consider for example 2025 - if the hedge is reinvested mechanically, the 5 year swaps that are maturing should be those put on the books in 2020 at yields below 1%. But they should now be reinvested at just shy of 4% - a 300bp uplift. With 20% of the book rolling over each year (1/5th) ballpark we could expect ‘product hedges’ to see an increase in yield of 50-60bp per annum (20% x (4%-1%)). And indeed that’s pretty much what Lloyds management are forecasting; a jump from 1.74% in 2024 to around 2.3% in 2025e and 2.9% in 2026e. The chart below shows my estimates (see blog part 2 for more discussion).

For some context, the total structural hedge sizes (product plus equity) for Barclays, Lloyds and NWG were GBP232bn, GBP244bn and GBP194bn respectively. Hence it’s easy to see why a 60bp uplift in the yield on these structural hedges can produce GBP1bn+ revenue improvements.

I feel it’s important to add at this point that the structural hedges should not be viewed as a standalone source of profits for the banking system across an interest rate cycle. After all, when interest rates rise, the bank ‘under-earns’ on net interest income compared with where it would be without the structural hedge (which takes time to reprice up). Then when interest rates fall, the bank will ‘over-earn’ as the structural hedge takes time to reprice down. It’s a smoothing process, we just happen to be at the stage in the cycle where the UK banks are seeing incremental benefits year on year now. But that’s really just income that would have appeared immediately as base rates rose in 2022-23 if the banks didn’t have structural hedges.

Forecasting is theoretically easy…

What we need to know is:

The yield on maturing swaps, in any given period. We can look back at swap yields from 5 years ago (for the product hedge) or 10 years ago (equity hedge) as a proxy here. But the banks often give some disclosure

The yield the bank can get on reinvesting in new swaps. There’s a degree of crystal ball gazing here. But readers should keep in mind that at its core the swap rate is essentially the money markets forecast of average base rates for the next 5 years. Hence if base rates are set stay in the 3-4% range in coming years then 5 year swap rates are likely to remain around 3.5% give or take.

The volume of swaps rolling over. Again we often get disclosure from the banks. But in the absence of that a good back-of-the-envelope assumption is 20% of the product hedge and 10% of the equity hedge (reflecting the 5 year and 10 year natures of them).

For anyone keen to explore this more, I have produced a simple structural hedge modeller spreadsheet that allows readers to play around with some of the assumptions above. That can be found here:

https://robindownblog.substack.com/p/structural-hedge-modeller

…but there are complications

By now we hope that readers have got the basics of the structural hedge - a rolling book of swaps designed to reduce the rate sensitivity of the bank. Forecasting should be easy if we had good disclosures from the banks or the hedges are reinvested entirely mechanically. The theory should hopefully be clearer now.

But there are inevitably complications when it comes to forecasting and to quote Donald Rumsfeld there are plenty of “known unknowns”. By no means an exhaustive list of issues include:

Changing hedge durations. The industry tends to talk in terms of 5 year swaps for product hedges. But there’s no particular reason why banks should hedge solely at the 5 year mark and indeed, management teams appear to often take a view on where the best value can be achieved. Barclays has recently talked about extending durations out longer. And if we look at the product hedge if it’s invested in 5 year swaps it should have an average duration of around 2.5 years (20% at year 1, 20% at year 2, 20% at year 3 etc). But I estimate Lloyds product hedge moved from an average 2.0 year duration in 2020 (so invested shorter term) to 3.3 year in 2021 (a sudden reinvestment in longer durations).

Trading. Linked to the duration point, the easiest way to forecast structural hedges is to assume a mechanical roll-over. On a 5 year book that allows us to look back 5 years to estimate maturing swap yields. But the banks do appear to “trade” their structural hedges to some degree, most notably the example above of Lloyds who (correctly) took the decision in 2020 not to reinvest in new 5 year swaps as yields were close to zero and instead held off until 2021 to reinvest. That adds an element of uncertainty as to what is maturing in future periods and at what yields.

Lack of disclosure. In an ideal world the banks would give us the major components (maturing yield, volume of maturities). But the disclosure varies from bank to bank. Indeed Lloyds tell us very little other than the expected improvement in the contribution of the hedge each year; while on the one hand that does make life a little easier, it does mean that it’s hard to see the moving parts and assumptions so that we can stress test them

A brief word on the Asian banks

Why has the discussion thus far been solely focused on the UK domestic banks - what about Standard Chartered and HSBC? The reason why I haven’t mentioned them thus far, is that up until quite recently neither bank has run a meaningful structural hedge (caveat: HSBC has run a traditional hedge in its UK operations). There are a number of reasons for this:

A lack of a HK government bond market. Putting aside short term bills (less than 364 day duration) issued by the HKMA there hasn’t really been a government bond market of note in Hong Kong. Indeed the first HK government bonds weren’t issued until 2009 and even now the institutional amounts outstanding are less than USD10Bn. Hence there’s no natural “fixed rate” asset in HK equivalent to the UK’s gilt market (and similarly swaps market)

A lack of alternative fixed rate assets. The HK mortgage market has been, and remains, a market entirely dominated by floating rate loans. We’ve seen attempts by the banks to try and introduced fixed rate mortgages (that could potentially be used by a hedge), including HSBC currently, but thus far take-up has been limited - we’d estimate less than 1% of mortgages outstanding are on fixed rates.

That combination has made running a HKD-based structural hedge difficult.

The one factor in the HK banks favour though is the currency PEG between the HK dollar and the US dollar (7.8:1). This has been in place for a few decades now and has withstood numerous attacks (I will write about the PEG and HK interest rates in a future blog). With the two currencies freely interchangeable at a fixed exchange rate, that lends itself to the possibility that HSBC and Standard Chartered could put a structural hedge in place for their HKD deposits with US-fixed rate assets (bonds and swaps).

Historically, I think there has been a reluctance to do this as it potentially leaves the banks exposed to an FX risk should the HKD PEG ever break or be voluntarily realigned. But in the last 3 years or so, the banks seem to have overcome those fears and began to put a HK structural hedge in place utilising USD financial assets.

We can see this build out in the table below which is based on Standard Chartered data. The bank’s structural hedge has quadrupled in size since 2021 from USD19bn to USD75bn (using predominantly treasury instruments like swaps). In addition the bank also identifies USD18bn of ‘client assets’ (read: fixed rate loans) as part of its interest rate hedging efforts. There’s been a similar build out at HSBC.

This recent build out of a structural hedge at both Standard Chartered and HSBC is great news from the perspective of reducing future interest rate sensitivity at the banks. However, the downside is that as most of the hedge has been put on recently, when rates were already high, we don’t see the same near-term upside from the hedge repricing (and hence one reason why the two HK bank structural hedges garner limited attention).

Consider Standard Chartered above. The yield on its hedge stood at 3.6% in 25H1. With the yield on 5 year US interest rate swaps currently standing at 3.5%, it feels like there’s limited upside for the bank from the hedge in terms of year on year revenue progression.

HSBC appears to be in a slightly better position; the Group estimates the yield on maturing swaps in 2026e will be 2.8% rising to 3.4% in 2027e so there’s some limited near-term scope for incremental gains this year, we’d estimate circa USD0.6bn versus 2025e. But for context that’s just over 1% of the consensus 2026e net interest income forecast for HSBC, so helpful but not a game changer (note: the likely structural hedge benefits for the UK domestic banks in 2026e are mid-high single digit percentage points).

In conclusion

This brings to an end the introduction to structured hedges. I’m hoping that for those new to the subject it helps clarify why banks have them (to smooth rates), what they’re made up of (a rolling book of swaps) and how they can lead to deferred benefits from rising rates. And finally why the two HK banks are somewhat less interesting, for the moment, in this area.

In a separate blog I will post my thoughts on the current structural hedge positions of the three UK domestic banks and any nuances to watch for in the next 12-24 months.

Robin Down

Addendum: swap/gilt equivalency

I’ve deliberately put this as a footnote to this blog as it’s not something that I believe readers should spend too much time on. But for who are interested…

Under the old system, where gilts were used, the transaction was simple. The bank took the interest free deposits it had collected and bought gilts in the market. It receives a fixed rate of interest on the gilt (and pays the current account holders zero).

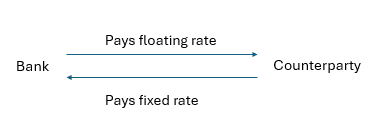

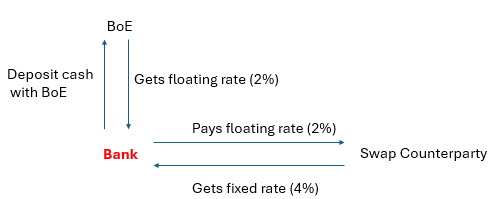

Under the “new” system banks instead use swaps. For those new to the subject an interest rate swap is a fixed/floating rate contract. The buyer of a 5 year interest rate swap - the bank in this case - agrees to pay the counterparty a floating rate of interest over a period of 5 years. And in return the counterparty gives the bank a fixed rate of interest for that 5 year period (the yield on the swap). The bank and the counterparty are “swapping” their income streams.

At first glance, this doesn’t look equivalent to the gilt route. After all, while the bank is receiving a similar fixed rate of interest to the gilt, it’s now having to pay the counterparty a floating rate of interest?

The key issue here is that entering an interest rate swap contract is a cashless transaction. In the gilt example the bank has to hand over cash to buy the gilt. But in the swap example there’s no upfront cash. Hence the bank can still use that elsewhere and if we assume it parks it on reserve with the BoE it will earn the same floating rate (base or SONIA) that it needs to pay to the Swap counterparty.

Consider an example - gilt/swap yields are 4% and floating rates (Base/SONIA) are at 2%. In the gilt example, the bank buys the gilt (earning 4%) and pays its depositors zero. Hence a net 4% interest spread.

But if the bank instead takes out a swap contract with a yield of 4%, it now has to pay the swap counterparty 2% per annum. But as the bank still has the cash from the deposits, it can park those with the BoE who will pay the bank 2%. The net interest spread is the same 4% as under the gilt route (4% minus 2% + 2%). QED

Thanks for this post. One thing I always wonder about is why US and European banks don’t have structural hedges?